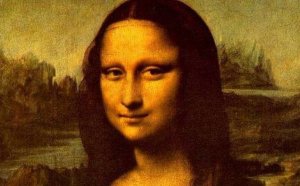

Images of Renaissance period

By 1600, there were over fifty miraculous images in Florence: weeping Madonnas, bleeding Christs, paintings and sculptures—often veiled and only occasionally exposed to direct view, surrounded by heaps of votive offerings left by the faithful in gratitude for miracles experienced. Their proliferation during the previous three hundred years in churches, oratories, and street tabernacles throughout the city occurred alongside the founding of many more cults across Florence’s hinterland, or contado. Indeed, as the commune extended its territorial domain, so the new subject-cities spawned miraculous images—a process of sacralization strongly supported by the Florentine regime.

With painstaking scholarship, Megan Holmes’s reconstructs the chronology of this devotional phenomenon. She identifies four main phases of development. The period from 1292 to 1398 witnessed the origins of the earliest cults, mostly centered on images of the Madonna and Child. The start of the second phase, which lasted from 1399 to 1493, coincided with the rise of the Bianchi—a popular religious movement, renowned for its barefoot processions in which crucifixes were carried. Given the high profile of the Bianchi in Tuscany, it is no surprise that this period should have resulted in new cults featuring crucifixes, some of which had started life as processional crosses. From the late fifteenth century, the pendulum swung back in favor of Marian cults. A crop of miraculous images of the Virgin arose during a period of political instability between 1494 and 1530, and in particular following the execution of Girolamo Savonarola in 1498. The return of the Medici to power in Florence in 1531 in their new role as hereditary rulers of the Florentine dukedom prompted a final phase of growth in the number of miraculous images venerated in the city that lasted until the end of the sixteenth century. During this period, the proliferation of cults sponsored by the Medici fused with the Counter Reformation impulse to promote both Marian and Christocentric devotions, albeit under more controlled conditions. Many of the new image cults were located within nunneries.

While Holmes’s work in tracing the complex histories of image cults in Florence and the contado is in itself to be commended, her engagement with chronology goes beyond establishing dates and trends. In fact, the book is an ambitious attempt to unsettle and reconfigure understandings of the Renaissance—as both concept and period—by viewing a key facet of cultural productivity in Florence through the lens of devotion. This is, needless to say, an anti-Burckhardtian Renaissance that banishes the idea of the era as harbinger of modernity and secularization and eschews the art-historical canon. While, in older accounts, miracle-working images tended to be dismissed as “archaic in style, imitative in form, poor in quality, compromised by repainting, and consequently of little art historical interest, ” Holmes here boldly argues that “image cults were among the most vital and dynamic sites of cultural activity in Renaissance Italy” (5–6).

True enough, the explosion of image cults coincided neatly with the period generally associated with the Tuscan Renaissance: from the second half of the thirteenth century, the age of Dante and Giotto, to the 1500s—the century of Michelangelo and Machiavelli, Vasari and Galileo. But Holmes is talking about more than coincidence. The novelty which we attribute to the Florentine greats was, she proposes, also evident at the shrines of miraculous images: “The material and visual culture of Renaissance Florentine image cults did not simply involve the recrudescence of earlier artistic and religious genres. . . . New categories of visual representation and innovative variations on traditional forms emerged” (10). Among these innovations, she includes the emergence of life-size votive portrait statues, small painted wooden panels representing miracles, elaborate all’antica tabernacles enshrining miraculous images, and illustrated printed miracle books.

In emphasizing the artistic innovation that was generated in the Florentine shrines, Holmes challenges the assumption that miracle-working images were Byzantine in style and—regardless of their actual date—aspired to look archaic. Yes, there were instances of Byzantine icons that manifested miraculous powers (the eleventh-century Nikopeia Madonna in San Marco, Venice, or the Holy Face in San Bartolomeo degli Armeni in Genoa, a contact relic which supposedly bore the impression of Christ’s face, set in a fourteenth-century frame, for example), but, according to Holmes, Byzantine and Byzantinizing icons represented “only a small percentage of Italian Renaissance miraculous images and an even smaller fraction of those found in the Florentine environs” (163). The fact that a brand new image could be just as effective as one deemed to be ancient or at least archaic in style is well illustrated by the case of Bernardo Daddi’s the Madonna of Orsanmichele, commissioned in 1347 to replace an earlier miraculous image that had been destroyed in a fire. Daddi’s Madonna, which has previously been characterized by art historians as self-consciously backward in style, recurs at key points in Holmes’s argument. She rejects the view of the painting as archaizing, and emphasizes instead the “monumentality, material richness . . . refined technique, and visual intimacy” of the work (149). Daddi was an accomplished artist who deployed his skill in order to create a “sacred object that eloquently articulated the beauty, grace, queenliness, and nurturing attitude of the Virgin” (235). Holmes’s argument, developed in relation to the miraculous images of Renaissance Florence, places her in the camp opposed to the view of Hans Belting that there is a rupture between the traditional cult images of the medieval period and true art, marked by individual invention, in the Renaissance.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

Share this Post

Related posts

List of Renaissance Paintings

The Early Italian Renaissance art refers to an artistic movement that started in Florence and other rich north Italian cities…

Read MorePainters in Renaissance period

The English Renaissance was a cultural and artistic movement in England dating from the late 15th to the early 17th century…

Read More