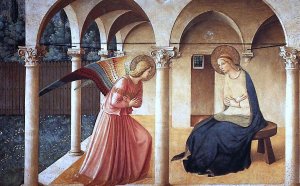

Proto Renaissance Art

Share this Post

Related posts

Simple Renaissance Art

MARCH 07, 2026

We live in a world that’s highly technical and specialized. When a man goes to college these days, he spends his time learning…

Read MoreFamous Renaissance Art

MARCH 07, 2026

The great painters of the Renaissance period, many of whom focused on religious themes were often commissioned by well-to-do…

Read More